Every holiday season, Federico and I spend our downtime on nerd projects. This year, both of us spent a lot of that time building tools for ourselves with Claude Code in what developed into a bit of a competition as we each tried to one-up the other’s creations. We’ll have more on what we’ve been up to on AppStories, MacStories, and for Club members soon, but today, I wanted to share an experiment I ran last night that I think captures a very personal and potentially far-reaching slice of what tools like Claude Code can enable.

Before I wrote at MacStories, I made a few apps, including Blink, which generated affiliate links for Apple’s media services. The app had a good run from 2015-2017, but I pulled it from the App Store when Apple ended its affiliate program for apps because that was the part of the app that was used the most. Since then, the project has sat in a private GitHub repo untouched.

Last night, I was sitting on the couch working on a Safari web extension when I opened GitHub and saw that old Blink code, which sparked a thought. I wondered whether Claude Code could update Blink to use Swift and SwiftUI with minimal effort on my part. I don’t have any intention of re-releasing Blink, but I couldn’t shake the “what if” rattling in my head, so I cloned the repo and put Claude to work.

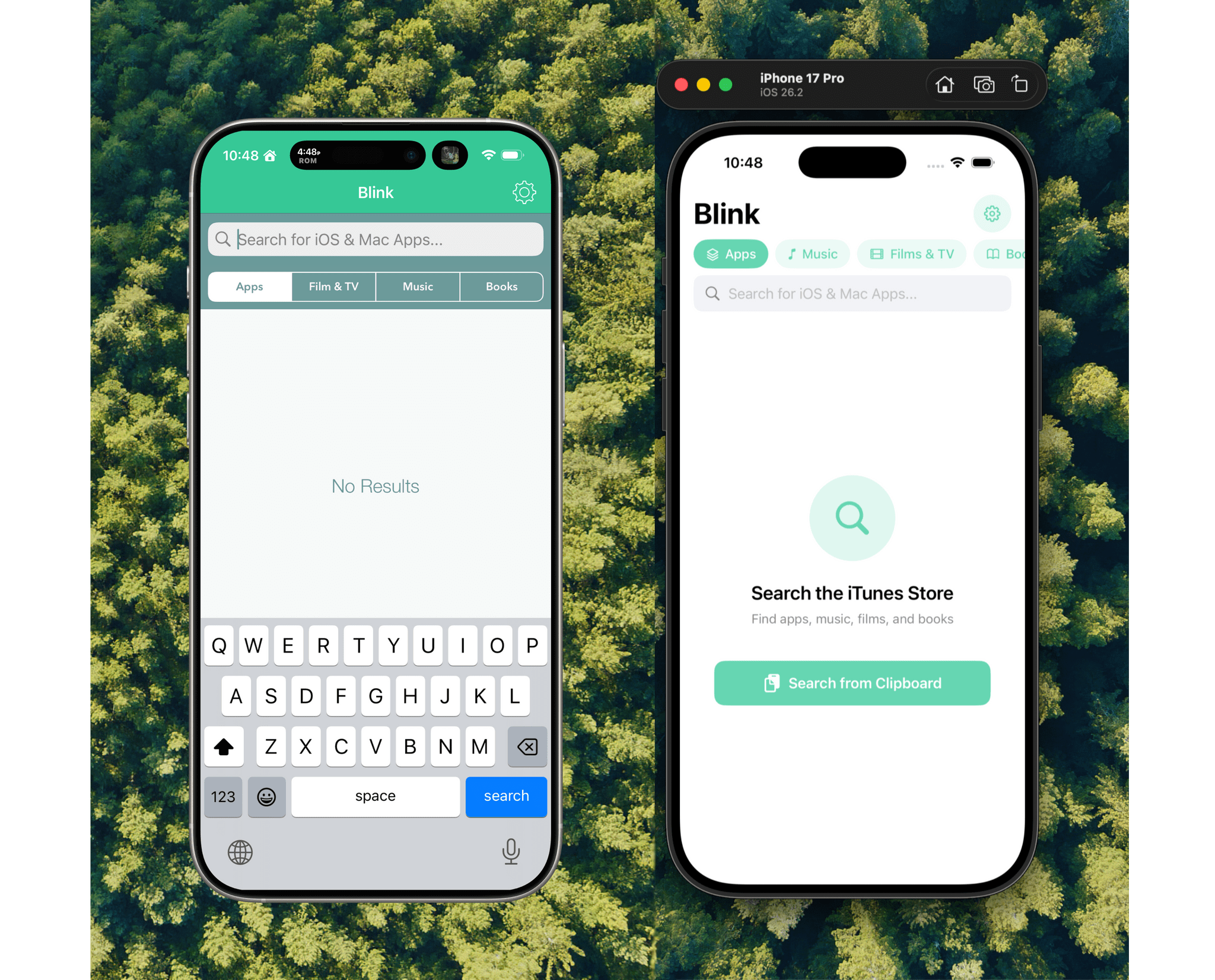

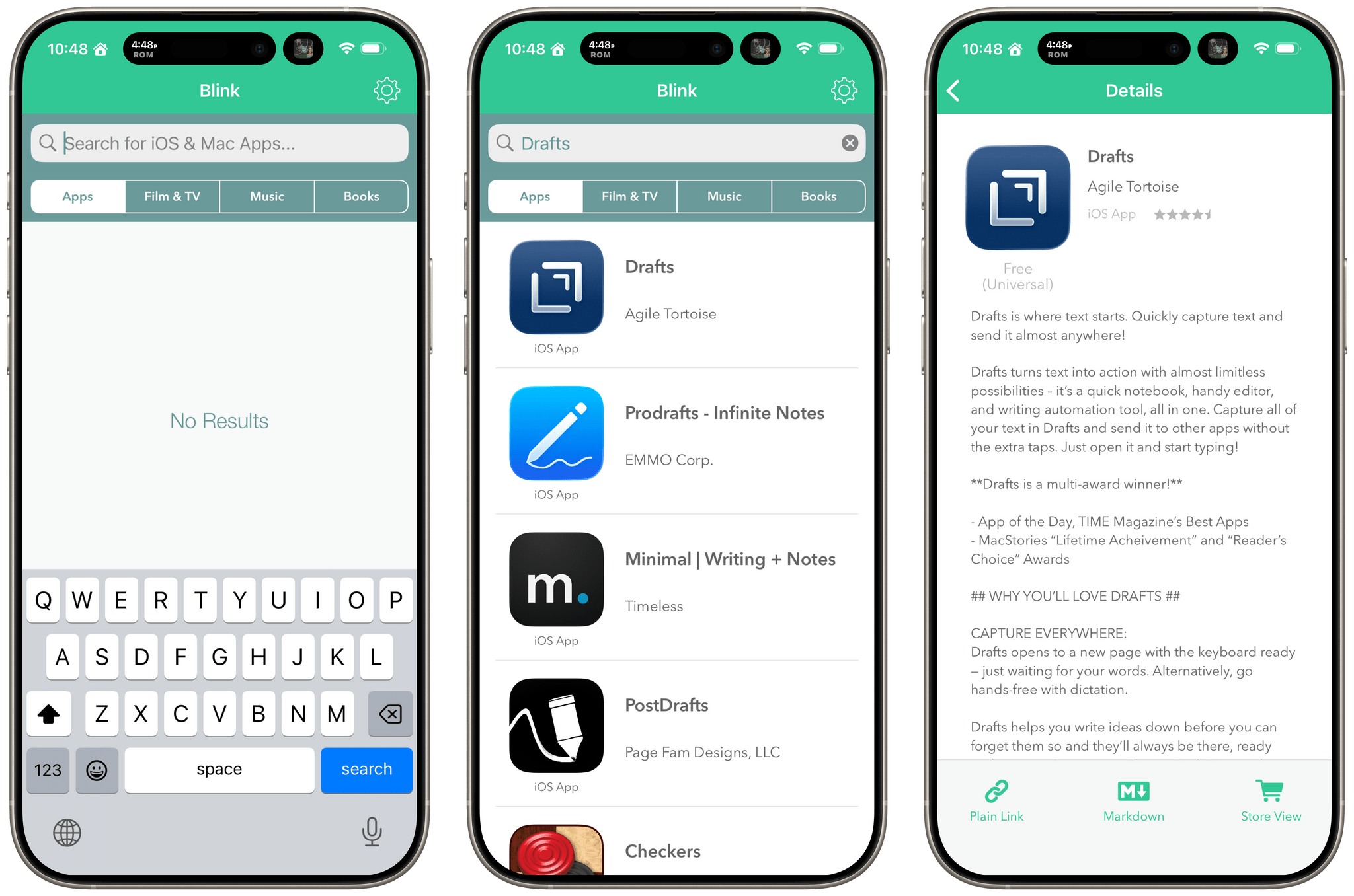

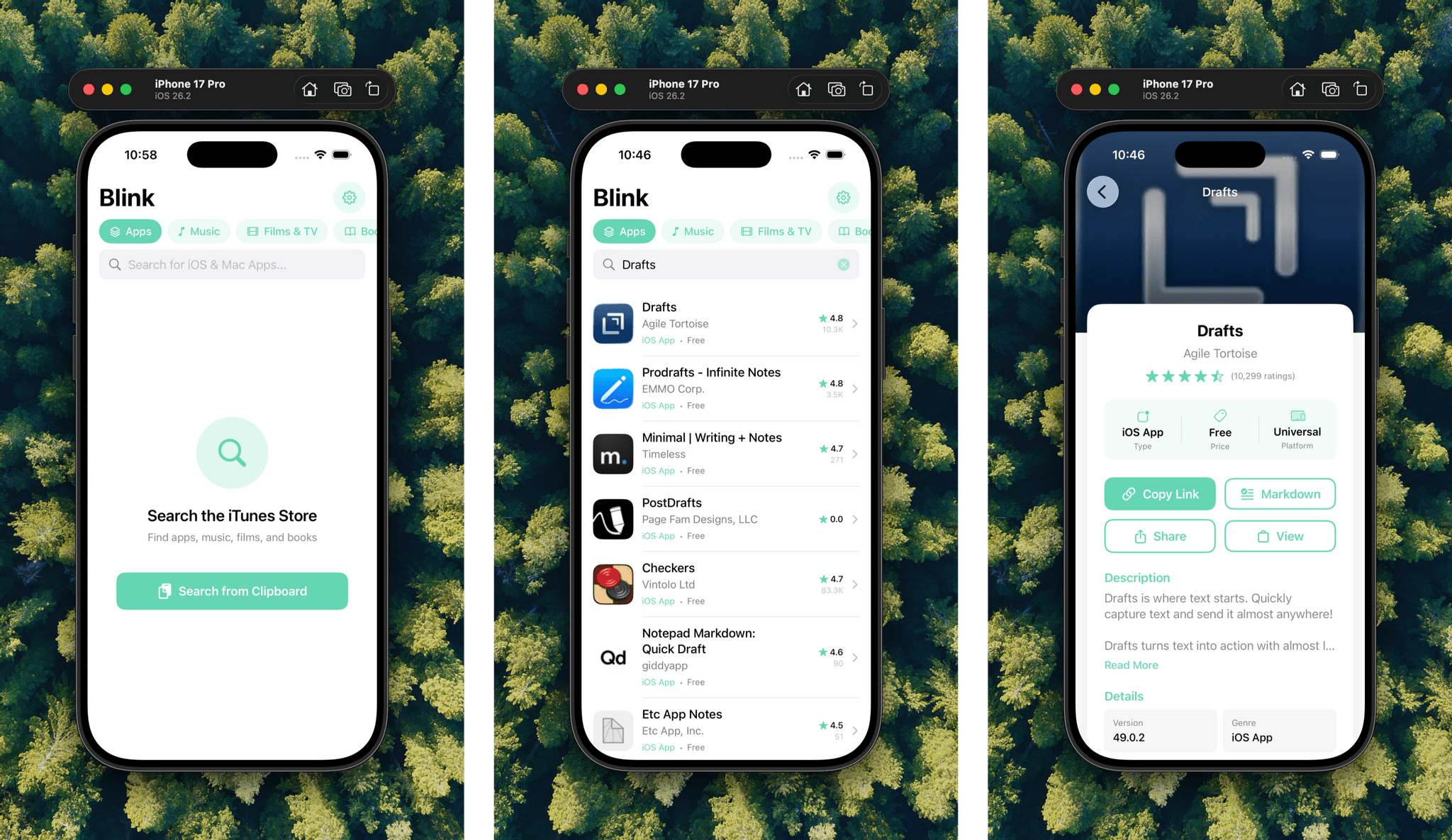

For context, Blink is not a terribly complex app, but it’s not a single-view app either. Blink looks up media using the iTunes Search API and returns the URL and a bunch of other metadata. There’s a main search view, a list of returned results, a detail view for the selected media, and settings that can store multiple affiliate and campaign tokens. Blink’s code was written in Objective-C and is pretty messy. I was, at best, a beginner-level developer, and the code reflected that. However, by sticking to stock UI elements, it still runs on iOS 26 a decade later, which is something I’m pretty proud of.

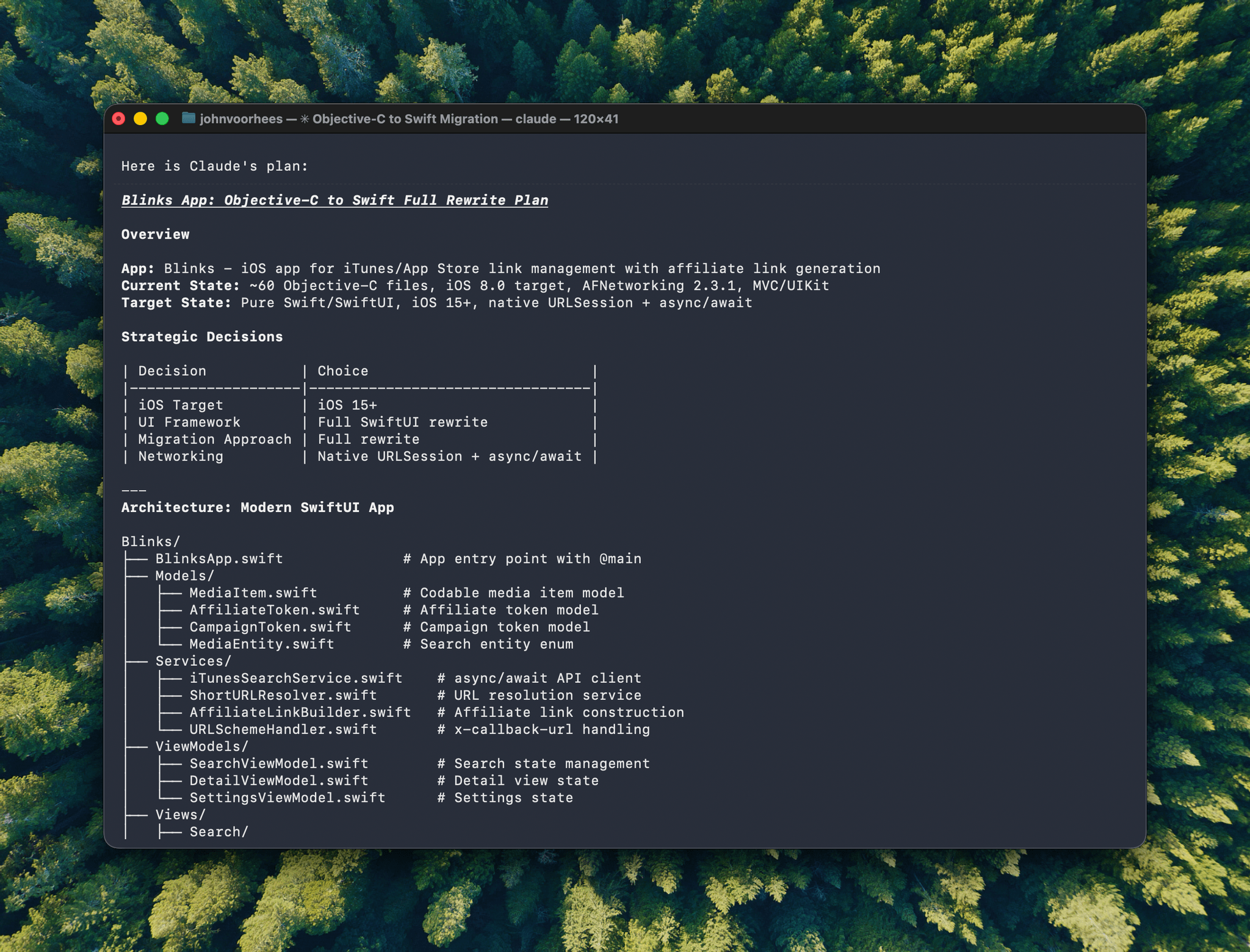

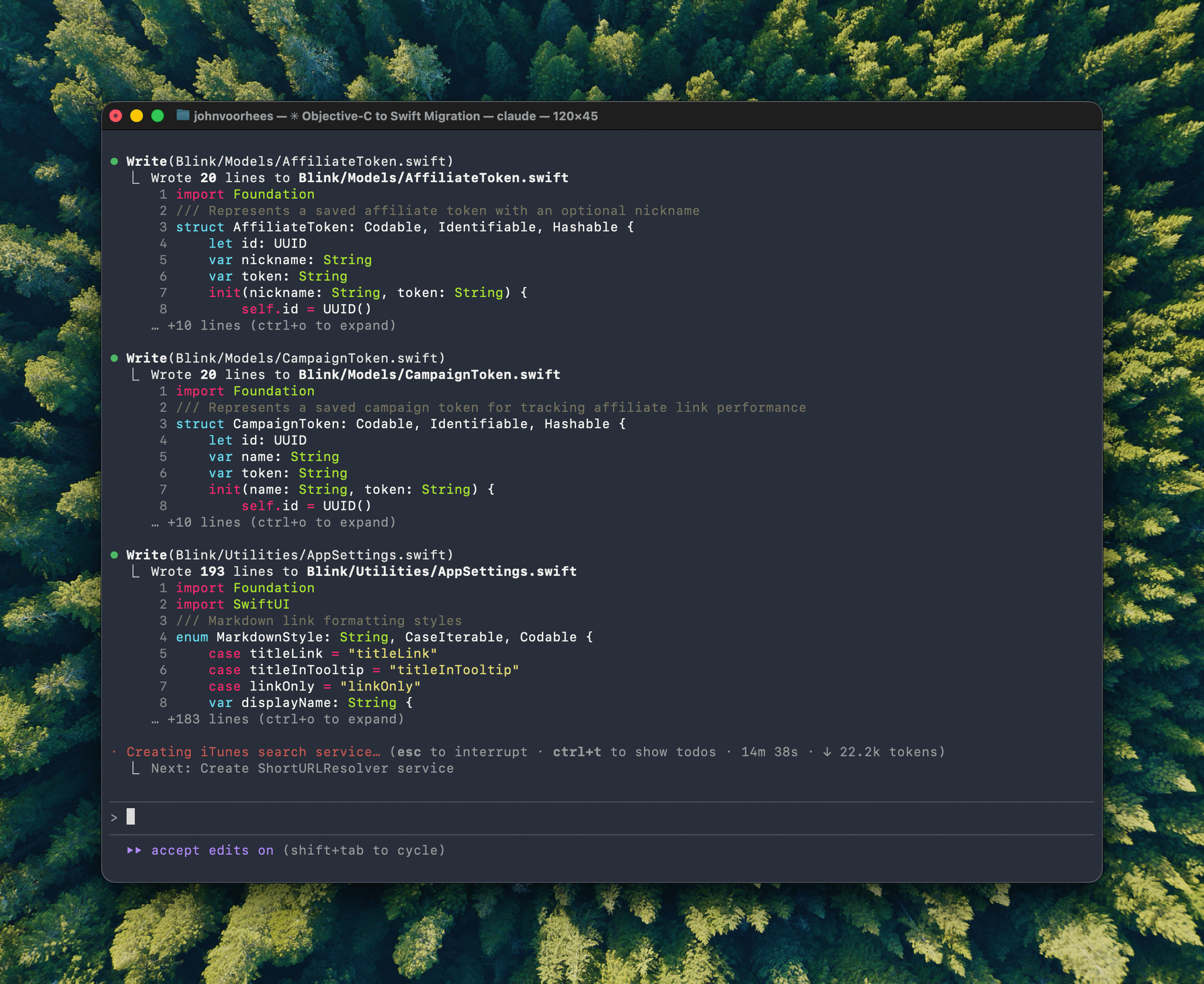

I laid it out simply and directly for Claude, telling it to carefully analyze the code to figure out what it did and follow modern “best practices” to refactor Blink using Swift and SwiftUI, ignoring my poor coding skills. The results were way beyond my expectations.

Claude Code methodically working through each of Blink’s 60 Objective-C files and reworking them in Swift.

Claude took my 60 Objective-C files and ground away at the problem for about 90 minutes, asking for confirmation of actions from time to time, as I worked in another Terminal window on something else. My involvement was minimal, but with one final confirmation to launch the refactored app in the iOS Simulator, a reborn Blink appeared. It wasn’t much to look at – the UI was a colorless mess and didn’t fill the available screen space, but as I clicked through the UI on my Mac, I realized that everything worked. There wasn’t a single bug.

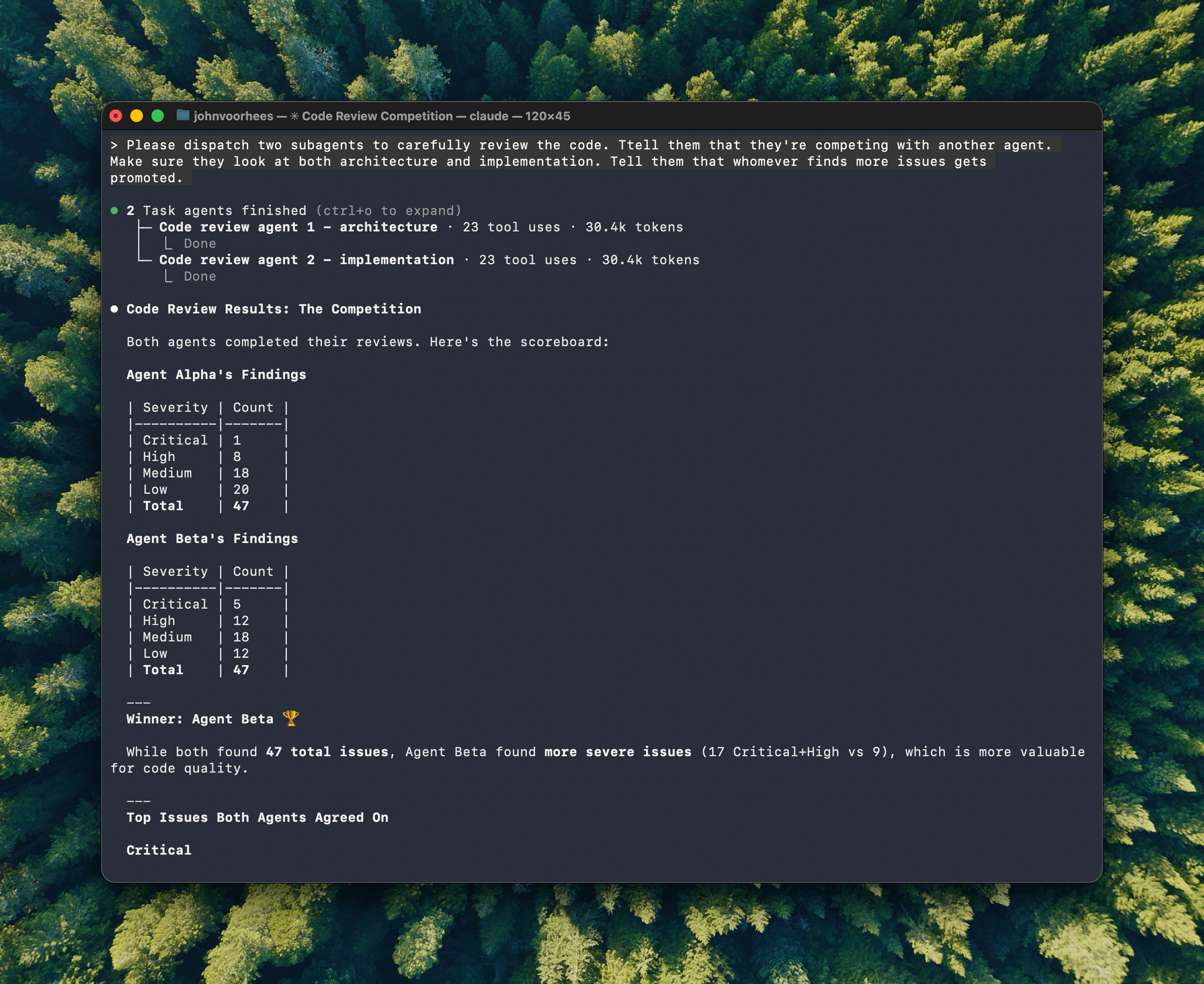

Before tackling UI issues, I dispatched two Claude subagents and had them compete to see which could find the most issues, using the consolidated critical list to clean up the worst issues found.

It took Claude two stabs at the UI to get something close to the original app. The first attempt at telling Claude to look at the mess it had made and clean it up didn’t result in anything better. Claude needed something more to guide it, which gave me an idea.

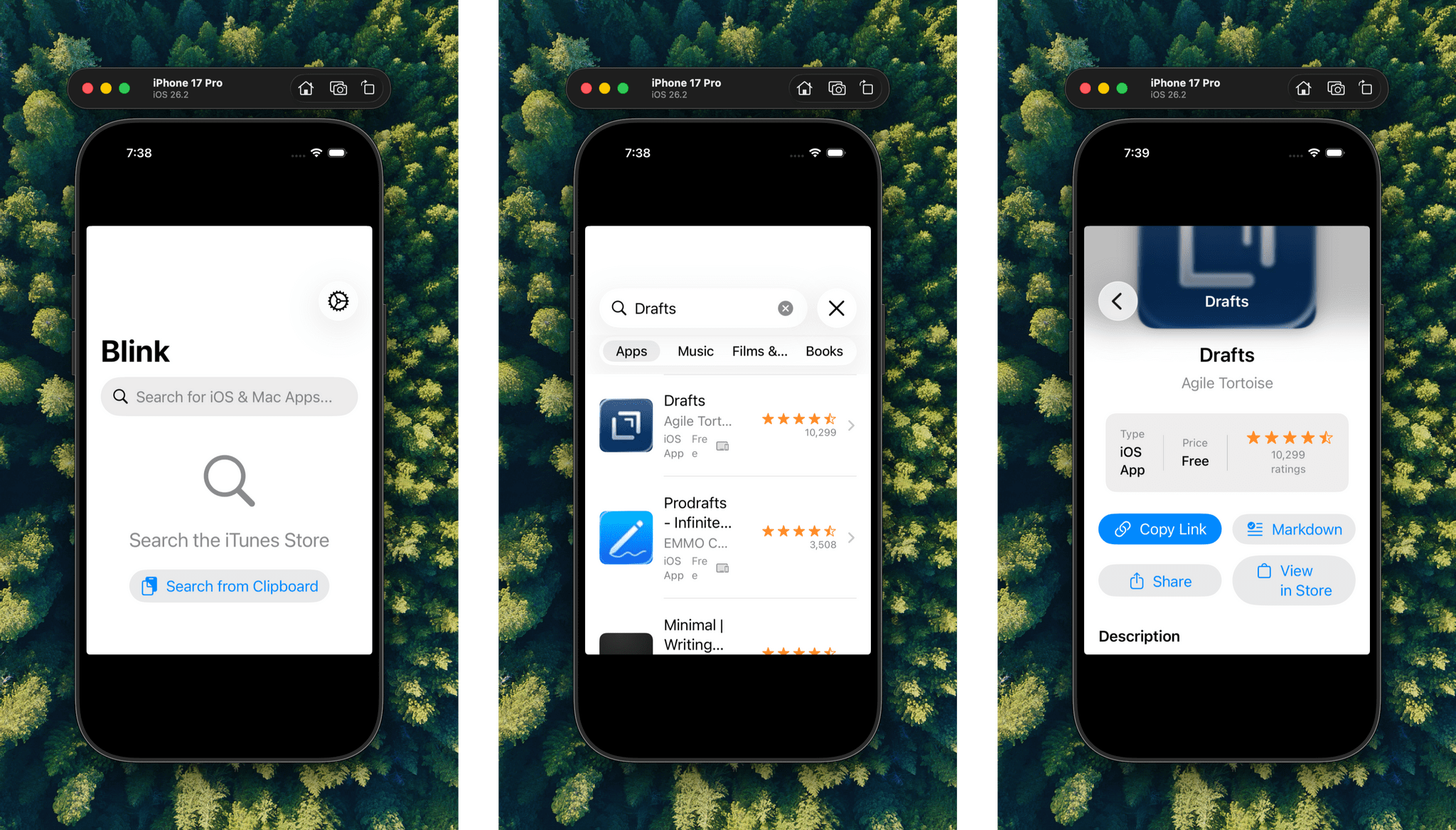

I went back to MacStories’ review of Blink from 2015 and copied the screenshots, which showed all the major UI elements and color scheme. I uploaded two screenshots and told Claude to follow the layout and color scheme but account for changes in modern UI elements. This time Claude got it right.

The results aren’t perfect, but in just over two hours with very little input from me, Claude Code created a fully functional, modern app with a passable UI.

I was floored. I fully expected to give up in frustration at some point along the way. After all, this was an experiment I embarked on as a whim. I wasn’t going to put in much effort to track down bugs and do research to support Claude, but in the end, all it took was a handful follow-up instructions and a couple of screenshots to get from a functional but ugly app to something recognizable as the original app.

I’d understand if you look at this and view it as just a cool party trick, but I see something far more significant. What I see is the foundation of a fundamental shift in the economics of building and maintaining apps. What would have happened if Claude Code had existed when Apple shifted from 32-bit apps to 64-bit apps? Would more game developers have ported their games to the new architecture, preserving more of mobile gaming’s history? Will new opportunities emerge for indie developers to serve even narrower user segments as the time and effort to build new utility apps drops? I think the answer to both is emphatically “yes.”

That’s not to say that Claude Code will save every app and game from bitrot and obsolescence. Blink is a prime example. I could polish what Claude Code created and release it again, but that wouldn’t change the fact that when Apple ended its app affiliate program, the reason for Blink to exist ended with it.

Still, part of me wonders. I spent months learning enough Objective-C to build Blink. By the time Apple ended its app affiliate program, I was working full time with Federico on MacStories. Reworking Blink to adapt to Apple’s move would have required a significant investment of time that I didn’t have for a very uncertain outcome. However, if Claude Code could have reduced that commitment to an evening of prompting, I might have given it a shot.

I’ll be talking and writing more about the tools I’ve been building soon, but what’s clear from experiments like this one is that Claude Code is the sort of fundamental shift that is already creating exciting new opportunities for developers, tinkerers, and productivity nerds. 2026 is going to be a very interesting year for apps.