Three months after the public launch of iCloud, I thought it’d be interesting to check upon the App Store and see how many developers have decided to enable iCloud integration for documents & data storage in their apps.

iCloud went live alongside iOS 5 and OS X 10.7.2 on October 12th, two days ahead of the iPhone 4S’ launch. In retrospect, iCloud’s public debut wasn’t without its issues and hiccups, but it was relatively smooth in the following days and Apple acted promptly to restore interrupted services for its users. Looking back, it’s just weird how many times iCloud Mail has been down, and continues to be unstable, whereas iCloud sync (for apps and data) has been fairly responsive and, at least on my side, always up. This says a lot about priorities, I guess.

In 107 days since iCloud went live, and 235 since Apple’s announcement at WWDC ‘11, it appears the majority of third-party developers are still considering whether or not iCloud is something worth investing their time – and customers’ money – or not. Those who have successfully implemented iCloud have done so in ways that require minimal user interaction, most of the times enabling sync capabilities through a single setting switch. Others have tried more complex solutions, often having to come up with separate tools to enable iCloud. Especially on the Mac, the fact that only apps sold through the Mac App Store can be directly integrated with iCloud isn’t helping developers who are still selling apps both on Apple’s App Store and their own website. Overall, there seems to be a shared trend among developers choosing to wait for Apple to clarify specific aspects of iCloud sync, improve the platform and fix some bugs that may prevent certain applications from being iCloud-enabled without requiring a major restructuring of the codebase on their end. Turning an iOS or Mac app into an iCloud-enabled app hasn’t turned out to be the 1-click process many, including me, wrongfully assumed when iCloud was previewed at WWDC last year.

Every app has its own way of storing local documents and user data. Some apps prefer keeping the original source of a document intact, say a .txt file, whilst others may apply their own file format to store documents and data internally in a proprietary database or multiple files, such as Evernote’s take on XML. There are pros and cons: keeping a universal file format such as plain text gets you more benefits in data portability; writing your own database structure allows you, as a developer, to do things exactly the way you want. What does this mean for iCloud?

Without getting too technical (also because my knowledge on the subject can only get you so far before I suggest you go read the developer documentation), the developers I’ve talked to explained that in the way iCloud syncs file, there may be some incompatibilities with apps that are based on complex databases and libraries. Apps that simply want to sync .txt files across multiple devices might be easier to port to iCloud, but then again there are always some aspects to consider such as conflicts, renaming a file, or getting a timestamp for the modification date when multiple devices are accessing iCloud. That’s not to say implementing iCloud is technically impossible for apps that are based on libraries, and not easily exportable files: below, I’ve collected some examples of apps that do just that, and quite cleverly too. However, getting to enable iCloud and make it reliable enough so that all kinds of apps can work with it without frustrating the user (who, in theory, never has access to the inner workings of iCloud) while at the same time providing the functionalities he or she expects.

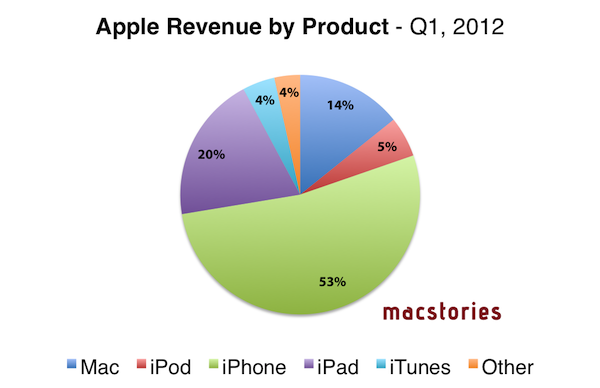

With 85 million users according to Apple, iCloud’s numbers aren’t too shabby. There are some details to consider when comparing iCloud-enabled iOS apps (quite a bit) to iCloud-enabled Mac apps (not so many) though: first is the popularity of iOS devices, which is just obvious when placing 37 million iPhones next to 5.2 million Macs. Just take a look at the revenue by product, and you’ll see that the potential of customer adoption because of devices sold with the App Store pre-installed is smaller on the Mac.

The majority of third-party developers are going where the money is – iOS – letting us wonder when we’ll see more Mac apps with iCloud support. I also believe that the reason the Mac is less prone to get a fast iCloud adoption lies in its history: users who are still running Leopard, a not-so-old OS, can’t upgrade to Lion unless they get Snow Leopard first, and this might have caused a slowdown in Lion upgrades and Mac App Store access. I could also add that, unlike iOS, Mac owners who did upgrade to 10.7.2 may not know about iCloud (or understand it) as it’s not thrown in their faces the way iOS 5’s new setup (rightfully) suggests to configure a device with an iCloud account. By design, iOS users are more likely to see, use, and understand iCloud, thus having interest in apps that supports it.

Last, Mac users are generally slower to upgrade to newer OSes than iOS users, and I wouldn’t be surprised to hear a lot of people still running Snow Leopard haven’t upgraded to Lion yet just out of laziness. Still: the Mac App Store reached 100 million downloads in less than a year.

From a developer’s perspective, there are other factors to consider. First off, many see iOS devices as a zero-risk platform to start developing for, especially if you’re creating a very simple app that among its default features has iCloud integration. Whereas on the Mac, I believe, users expect a certain grade of complexity and functionality from a third-party app, and quick $0.99 hits aren’t nearly as popular as they are on iOS. Furthermore, because iCloud is Mac App Store-only, developers who still sell apps on their website but would like to enter the Mac App Store and offer iCloud will have to support two different codebases, which means double the effort.

I asked on Twitter about iCloud-enabled apps for Mac and iOS. Unsurprisingly, several readers said they didn’t even know Mac apps with iCloud support existed, and those who did likely said they were only using iA Writer with such functionality.

Among the apps mentioned, it’s easy to spot the usual suspects we’ve covered before:

- OmniFocus for iPhone added “iCloud Capture” to automatically get new items from a Reminders list.

- GoodReader creates an iCloud document folder where you can drop any file you want.

- Instacast syncs settings and playback position across iPhone and iPad.

- Appigo Todo syncs tasks between the Mac and iOS.

- Consume keeps settings in sync with iCloud.

- iA Writer, the most popular choice, keeps documents in sync through an iCloud list on iOS and OS X.

- Day One recently added the ability to keep your journal synchronized with iCloud (note that if you choose iCloud sync, you have to disable Dropbox).

- A plethora of games now allow you to sync saved data with iCloud (this is fantastic, and long overdue).

As for apps that will support iCloud but aren’t out yet, The Omni Group has confirmed that new versions of OmniOutliner, OmniGraffle and OmniGraphSketcher will come with a new document manager to sync files with iCloud. Supposedly, this system will be similar to iWork and other document-based apps such as PDFpen, which display synced documents (with sync indicators) in their start page. Ideas On Canvas announced today both MindNode and MindNode touch will support exactly this kind of iCloud interface, and we can only assume The Omni Group will do the same with its Mac updates to the apps mentioned above. A note on PDFpen: because the app is available both on the Mac App Store and the devs’ website, Smile chose to give non-Mac App Store customers an easy way to enjoy iCloud support without buying the app again: they released a cheap standalone utility to sync documents to the desktop with iCloud. This utility is a document-based iCloud picker that comes built-in when you purchase the Mac App Store version of PDFpen.

When iCloud was first announced, some of us thought developers would rush to add support to their applications as the service seemed just too good to be true. It turns out, iCloud itself is a fantastic addition to iOS 5 for the end user, but between concerns on Apple’s long term plans and de-facto technical limitations, we might have to wait a little longer to have all our apps iCloud-ready, fine-tuned for an optimal experience.