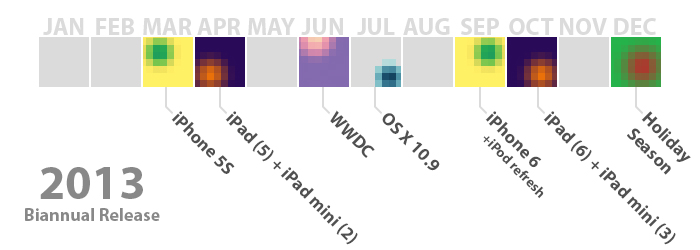

Just over a month ago, Horace Dediu of Asymco penned an article entitled ‘Does S stand for Spring’ in which he hypothesised that perhaps Apple might be moving to a biannual (twice-yearly) release cycle for the iPhone and iPad. Over the past month I’ve gone back to read Dediu’s hypothesis as news articles and analyst opinions surfaced and I did some analysis of Apple myself. It’s got to the point that I really think Dediu’s hypothesis has got real potential to become reality. So I decided to take some time to present Dediu’s evidence in a slightly different way, elaborating on some of his evidence and hopefully add to the discussion. But if you haven’t read the Asymco article yet, I’d highly recommend you do so before proceeding:

Posts in stories

Could Apple Be Moving To Twice-Yearly iPhone & iPad Releases?

Mapping Apple’s International iPhone & iPad Rollouts

Apple has on three seperate occasions announced that the iPhone 5 will have the fastest international rollout of any iPhone ever - at the announcement keynote, during the Q4 earnings call, and in their press release announcing opening weekend sales of the iPhone 5 in China. The claim was, no doubt, meant to impress investors, press and the general public, but I was curious as to how fast it really was compared to previous iPhone rollouts. So I decided to track down the launch schedules of all the iPhones to date and then again with the iPad. In the end I found a few trends, some oddities and that Apple’s claim was (mostly) true.

iPhone 5 will be available in more than 100 countries by the end of December, making it the fastest iPhone rollout ever.

Mac App Store: Year Two

Today, the Mac App Store turns 2.

Last year, I concluded my retrospective of one year of Mac App Store wondering whether 2012 would see more developers struggling to get their Mac apps approved for sale.

The Mac App Store is not without its flaws, and questions loom ahead as to whether Apple will lock down the system eventually — allowing customers to only install apps from the Mac App Store (as also recently suggested by Adam Engst on Macworld) — and cause a general confusion among developers and consumers as sandboxing is enforced and apps will need to comply to a stricter set of rules to be accepted on the Mac App Store.

A full year after that post, I believe it’s safe to say one word epitomizes Apple’s 2012 with the Mac App Store: uncertainity. Read more

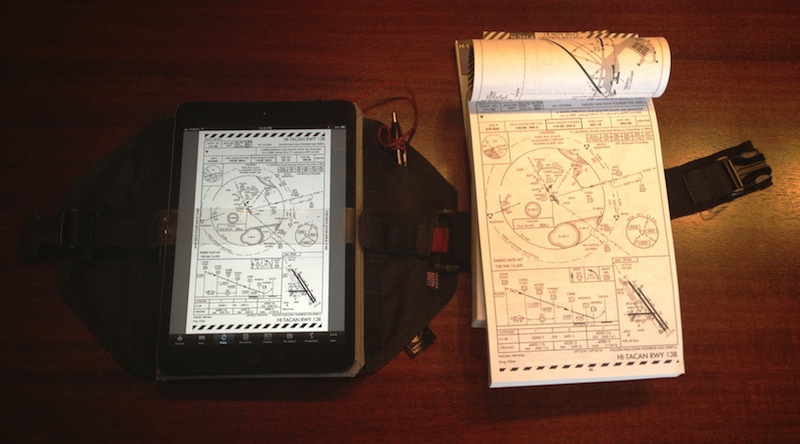

iPad in Real Life: Erik Hess, F-5N Tiger II Pilot

I believe people aren’t using iPads only as devices to “watch videos” or “catch up on reading”. Perhaps many people are; but there are some individuals who, thanks to the power and portability of the iPad, have managed to fit the device into their workflows and personal lives in ways that most of us wouldn’t expect. I think these stories deserve to be told. And they need to be told by the people who experience them first-hand.

For the first installment of a (non-regular) “iPad in Real Life” series, I asked Erik Hess to show me how the iPad has improved his flying experience in the cockpit.

Erik Hess spent 13 years as a pilot in the US Navy flying F–14B Tomcats and F/A–18E/F Super Hornets from aircraft carriers. He’s now a full-time designer and partner at high90 and continues to fly the F–5N Tiger II as an adversary pilot in the US Navy Reserve. He posts occasionally at his blog The Mindful Bit and you can find him on Twitter.

I asked Erik to share his experience in using the iPad as a flight-aiding tool in the cockpit. The result is a detailed account written by Erik himself covering a wide range of aspects from software used and replacing paper charts to portability and the importance of the Retina display. Perfect for what I was looking for, I left Erik’s thoughts mostly untouched because I believe, for this series, I should let these voices speak for themselves. Aside from minor editing, I chose to offer Erik’s own story, rather than my summary of it.

Mapping Apple’s Retail Expansion

Apple opened its first retail stores on May 19, 2001 - one in Virginia and the other in California. In the Steve Jobs biography, author Walter Isaacson wrote how Jobs had wanted Apple to have its own stores so that their iMacs didn’t have to “sit on a shelf between a Dell and a Compaq while an uninformed clerk recited the specs of each”. Despite initial criticisms and comparisons to Gateway’s failed retail stores, Apple Stores not only continue to exist today, but are regarded as one of Apple’s greatest innovations - one that now contributes to more than 10% of Apple’s revenue.

“Unless we could find ways to get our message to customers at the store, we were screwed.” - Steve Jobs

I’ve previously written about the coverage of Apple’s entertainment services in international markets (including how they compare to Google, Microsoft and Amazon), so I was similarly intrigued by how Apple’s stores have expanded into countries outside the US. Whilst researching all this, I came across other questions such as whether Apple had a particular preference for when they opened new stores and how the expansion of their retail network would affect visitors and profits. What I have found isn’t particularly groundbreaking, but there are certainly some trends and fascinating tidbits that I’ve come across, all of which is detailed below the break.

A note to RSS readers: This article includes an HTML5 diagram that likely won’t display in your reader, view this post in your browser (it works on iOS devices) to view that diagram. Apologies for the inconvenience.

Mapping The Entertainment Ecosystems: A Brief Revisit

In mid-October, we published a story on the entertainment ecosystems of Apple, Microsoft, Google and Amazon - looking at to what degree their music, movie, TV, eBook and app stores were available in international markets. Apple on the whole seemed to have the best average availability - slightly losing to Microsoft for the app stores and Amazon dominating everyone in the eBook store.

I’ve decided to briefly revisit the topic today because the original post garnered quite a lot of discussion and feedback and because of two “events” that have since happened. Firstly, Apple yesterday announced an expansion of the iTunes Music Store into dozens of new countries (and Movie store in a few additional countries). Secondly, I have since found two pieces of data on which countries Xbox Music is available in (for some odd reason I cannot find any official Microsoft document detailing the countries it is available in). So below is an update to the Music and Movie diagrams and graphs.

Note: Read the original ‘Mapping the Entertainment Ecosystems’ post which includes diagrams for eBooks, TV and App Stores.

Read more

Slogger and Day One Memories

Slogger is a fantastic script created by Brett Terpstra. With a bit of manual setup, Slogger can run on your Mac and, on a daily basis, pull entries from various Internet sources – such as Twitter and RSS – and put them into Day One automatically. It is a way to fill Day One with social updates for stuff that you write elsewhere. Brett is awesome, he’s working on new stuff for Slogger, and you should definitely check it out (and consider a donation) if you’re interested in its functionality.

I, however, have turned Slogger off a couple of weeks ago and removed the entries it created. This happened soon after the release of Day One with tags and search, which made me realize “automated logging” is not for me. Slogger was a placebo, not a medicine to let me write more. Somewhat intrigued by its scriptability and automation, I fell short of my own promise:

In twenty years, I’m not sure I’ll be able to remember the songs I like today, or the faces of people that I care about now. I don’t even know if I’ll be around in twenty years. But I do know that I want to do everything I can to make sure I can get there with my own memories. We are what we know. And I want to remember.

It took a while for me to realize I wasn’t fixing the right problem. Instead of making an effort to document memories I care about, I was passively watching another Internet pipe feeding a digital archive of my life with tweets, liked items, starred posts, and everything in between. Brett is awesome, but Slogger is not for me. At least not with the current version of Day One, because there’s no way to meaningfully separate “social entries” from “actually-written-by-me entries”. My wish is for Slogger to eventually mature into a standalone app for “social archiving”, separate from Day One.

I want my thoughts – not my stupid Twitter jokes – to be read by someone who, for some reason, will care about the life I had. There are several aspects of my digital life that I like to improve, but I won’t automate my memories.

Day One is a personal experience, and as such, I want it to be mine.

Half Full Glass

Some people think Apple will eventually “dumb down” OS X and make it a “more casual” platform not suited for power users.

I disagree.

I covered this recurring theme in a section of my Mountain Lion review:

I think the Mac power user will be just fine using Mountain Lion. In practical terms, Mountain Lion’s new features and design choices haven’t hindered my ability to install the apps I want, run macros to automate tedious tasks, or fly through applications using keyboard shortcuts. I prefer Scrivener to Apple’s Notes app, I rely on Keyboard Maestro to be more efficient, and I keep my notes in Dropbox rather than iCloud. On the other hand, I can jot down a quick todo in Reminders knowing instantly that it will “just work”, and I can pick up any conversation I was having on my iPhone thanks to Messages on my Mac. Making the entire operating system more cohesive and refined hasn’t diminished the relevance and utility of third-party software on my Mac; if anything, it’s made the key apps and functionalities I rely on better.

The argument usually goes something like this: iOS is so successful, Apple will eventually make Macs more like it. Plus, Gatekeeper and Sandboxing are signs that this will happen.

Usually, this piece by Rands in Repose is cited as a somewhat obvious confirmation to the fact that Apple is not afraid of “cannibalizing itself”.

This argument needs to be deconstructed on multiple levels. Read more

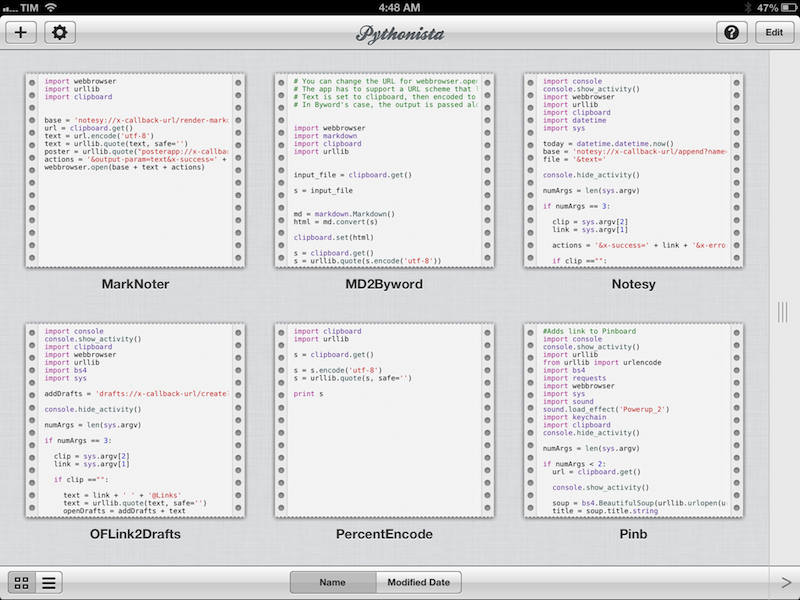

Automating iOS: How Pythonista Changed My Workflow

A couple of months ago, I decided to start learning Python.

I say “start” because, as a hobby to fit in between my personal schedule and work for the site, learning the language is still very much a work in progress. I hope I’ll get to an acceptable level of knowledge someday. Coming from AppleScript, another language I started researching and playing with earlier this year, the great thing about Python is that it’s surprisingly easy to pick up and understand. As someone whose job primarily consists of writing, I set out to find how Python could improve my workflow based on text and Markdown; I found out – and I’m still finding out – that Python allows for more flexible and intelligent string manipulation[1] and that some very smart folks have created excellent formatting tools for Markdown writers.

But this article isn’t strictly about Python. Soon after I took my decision to (slowly) learn my way around it, I asked my friend Gabe Weatherhead about possible options to write and execute Python scripts on iOS. Thanks to Gabe’s recommendation I installed Pythonista, and this app has completely changed my iOS workflow. Read more