Joe Steel makes a good point in his look at this week’s Apple TV announcements:

Why is TV the app an app and not the Home screen on the device? It’s obviously modeled after the same ideas that go into other streaming devices that expose content rather than app icons, so why is this a siloed launcher I have to navigate into and out of? Why is this bolted on to the bizarre springboard-like interface of tvOS when it reproduces so much of it?

You could argue that people want to have access to apps that are not for movies or TV shows, but I would suggest that that probably occurs less often and would be satisfied by a button in the TV app that showed you the inane grid of application tiles if you wanted to get at something else.

As I argued yesterday on Connected, I think the new TV app should be the main interface of tvOS – the first thing you see when you turn on the Apple TV. Not a grid of app icons (a vestige of the iPhone), but a collection of content you can watch next.

It’s safe to assume that the majority of Apple TV owners turn on the device to watch something. But instead of being presented with a launch interface that highlights video content, tvOS focuses on icons. As someone who loves the simplicity of his Chromecast, and after having seen what Amazon is doing with the Fire TV’s Home screen, the tvOS Home screen looks genuinely dated and not built for a modern TV experience.

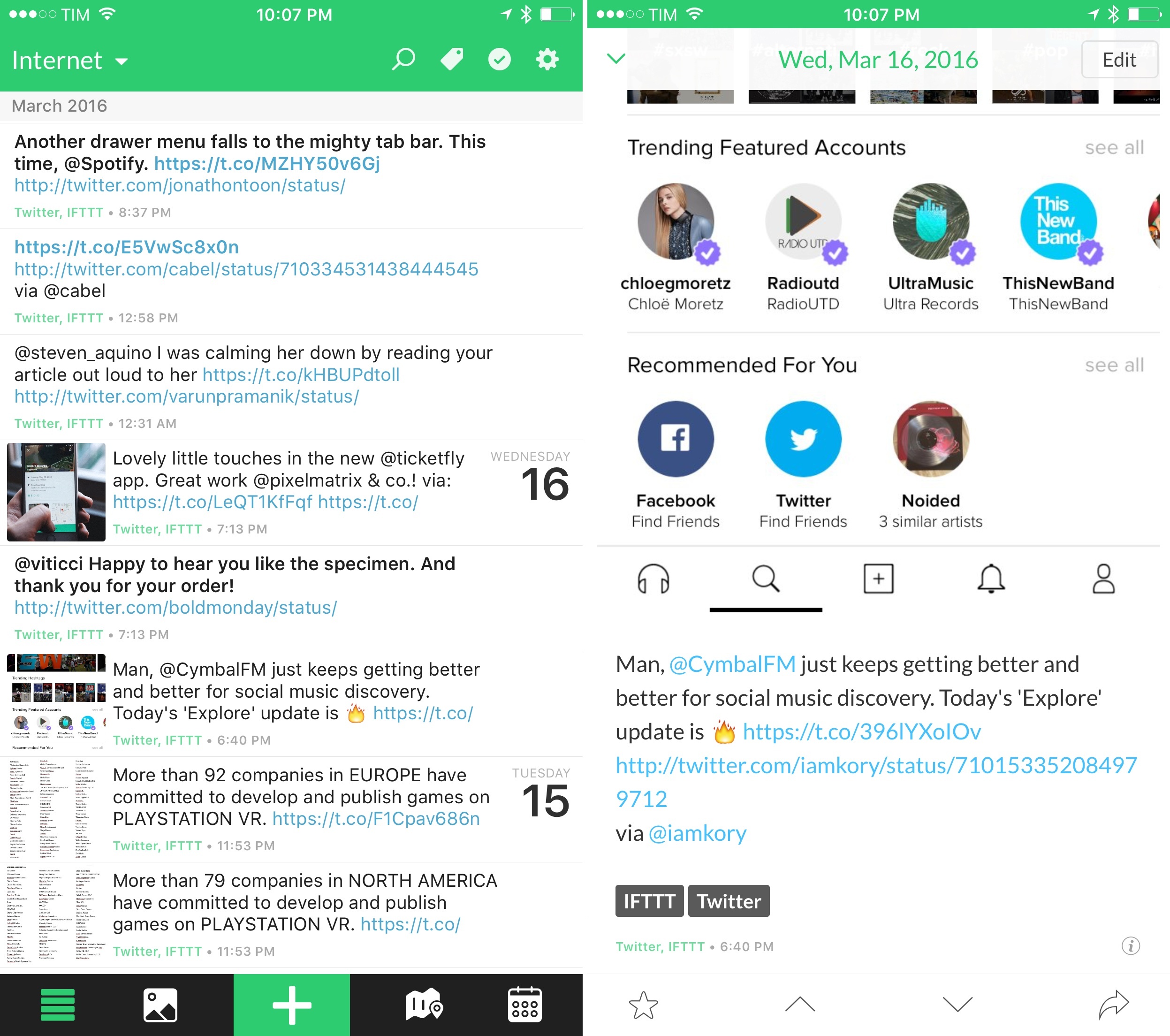

I think Apple has almost figured this out – the TV app looks like the kind of simplification and content-first approach tvOS needs. But by keeping it a separate app, and by restricting it to US-only at launch, Apple is continuing to enforce the iPhone’s Home screen model on every device they make (except the Mac).

That’s something the iPad, the Watch1, and the Apple TV all have in common – Home screen UIs lazily adapted from the iPhone. I wish Apple spent more time optimizing the Home screens of their devices for their different experiences.