Update, February 6: I’ve published an in-depth guide with advanced tips for secure credentials, memory management, automations, and proactive work with OpenClaw for our Club members here.

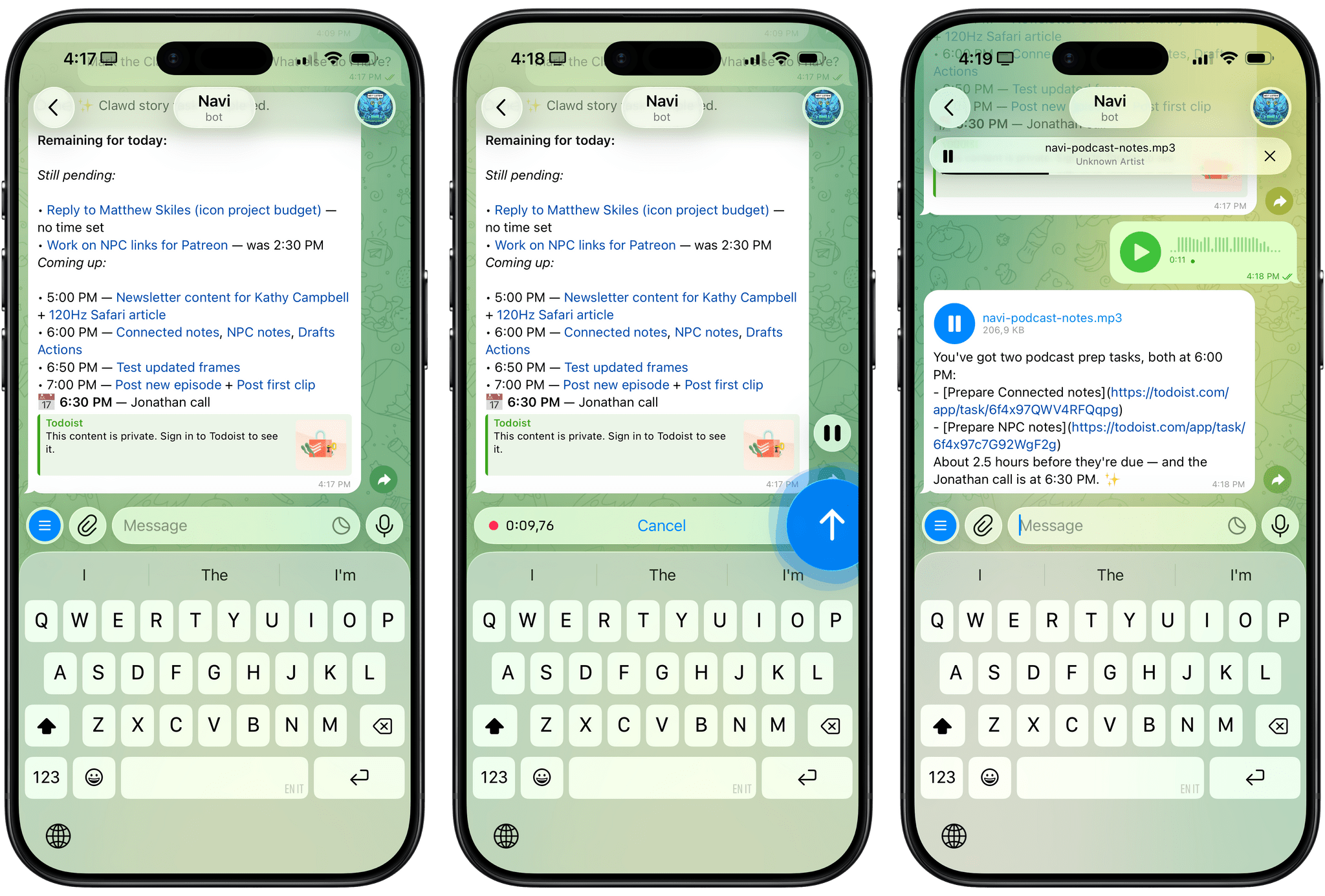

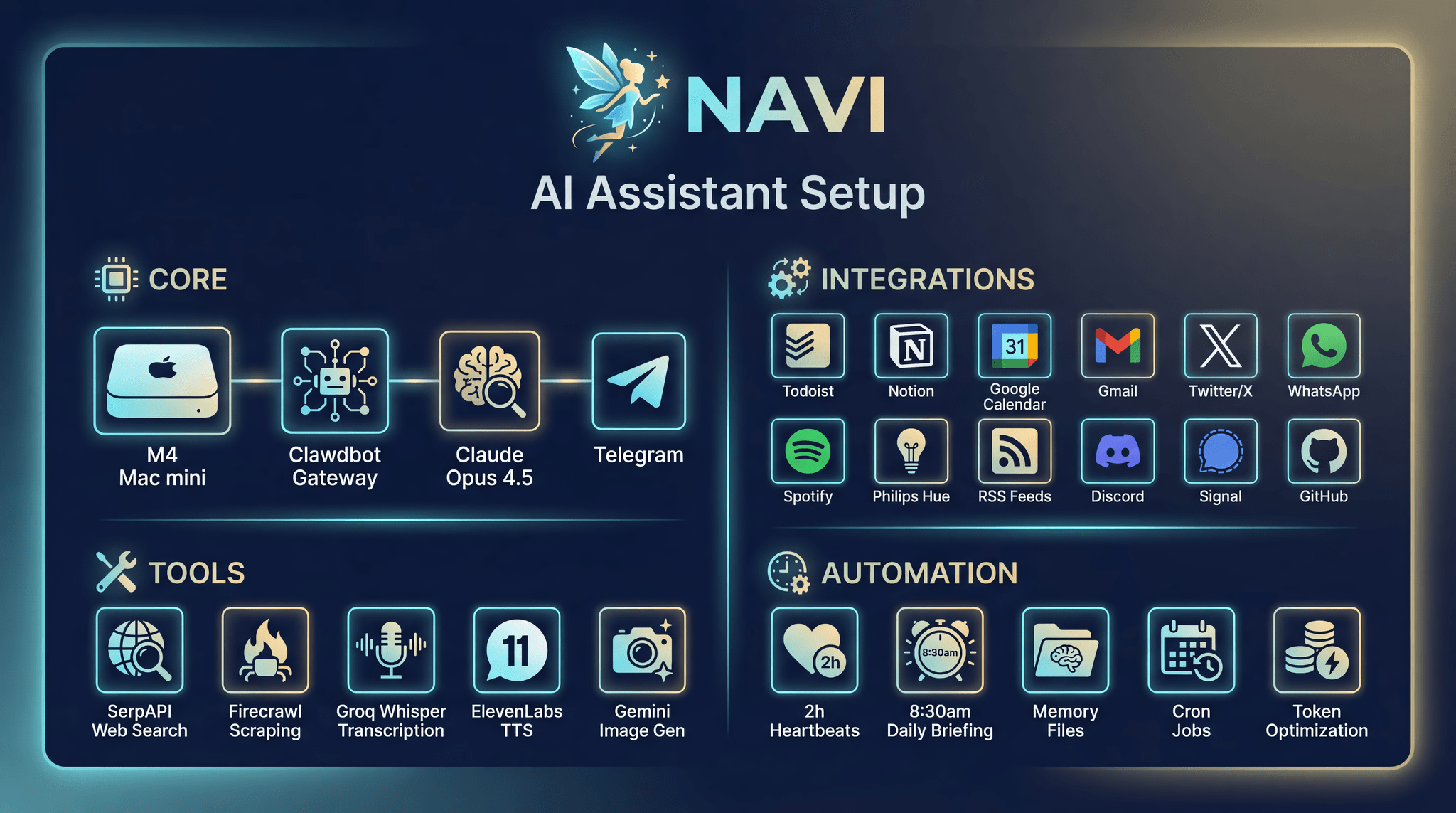

For the past week or so, I’ve been working with a digital assistant that knows my name, my preferences for my morning routine, how I like to use Notion and Todoist, but which also knows how to control Spotify and my Sonos speaker, my Philips Hue lights, as well as my Gmail. It runs on Anthropic’s Claude Opus 4.5 model, but I chat with it using Telegram. I called the assistant Navi (inspired by the fairy companion of Ocarina of Time, not the besieged alien race in James Cameron’s sci-fi film saga), and Navi can even receive audio messages from me and respond with other audio messages generated with the latest ElevenLabs text-to-speech model. Oh, and did I mention that Navi can improve itself with new features and that it’s running on my own M4 Mac mini server?

If this intro just gave you whiplash, imagine my reaction when I first started playing around with OpenClaw, the incredible open-source project by Peter Steinberger (a name that should be familiar to longtime MacStories readers) that’s become very popular in certain AI communities over the past few weeks. I kept seeing OpenClaw being mentioned by people I follow; eventually, I gave in to peer pressure, followed the instructions provided by the funny crustacean mascot on the app’s website, installed OpenClaw on my new M4 Mac mini (which is not my main production machine), and connected it to Telegram.

To say that OpenClaw has fundamentally altered my perspective of what it means to have an intelligent, personal AI assistant in 2026 would be an understatement. I’ve been playing around with OpenClaw so much, I’ve burned through 180 million tokens on the Anthropic API (yikes), and I’ve had fewer and fewer conversations with the “regular” Claude and ChatGPT apps in the process. Don’t get me wrong: OpenClaw is a nerdy project, a tinkerer’s laboratory that is not poised to overtake the popularity of consumer LLMs any time soon. Still, OpenClaw points at a fascinating future for digital assistants, and it’s exactly the kind of bleeding-edge project that MacStories readers will appreciate.

OpenClaw can be overwhelming at first, so I’ll try my best to explain what it is and why it’s so exciting and fun to play around with. OpenClaw is, at a high level, two things:

- An LLM-powered agent that runs on your computer and can use many of the popular models such as Claude, Gemini, etc.

- A “gateway” that lets you talk to the agent using the messaging app of your choice, including iMessage, Telegram, WhatsApp and others.

The second aspect was immediately fascinating to me: instead of having to install yet another app, OpenClaw’s integration with multiple messaging services meant I could use it in an app I was already familiar with. Plus, having an assistant live in Messages or Telegram further contributes to the feeling that you’re sending requests to an actual assistant.

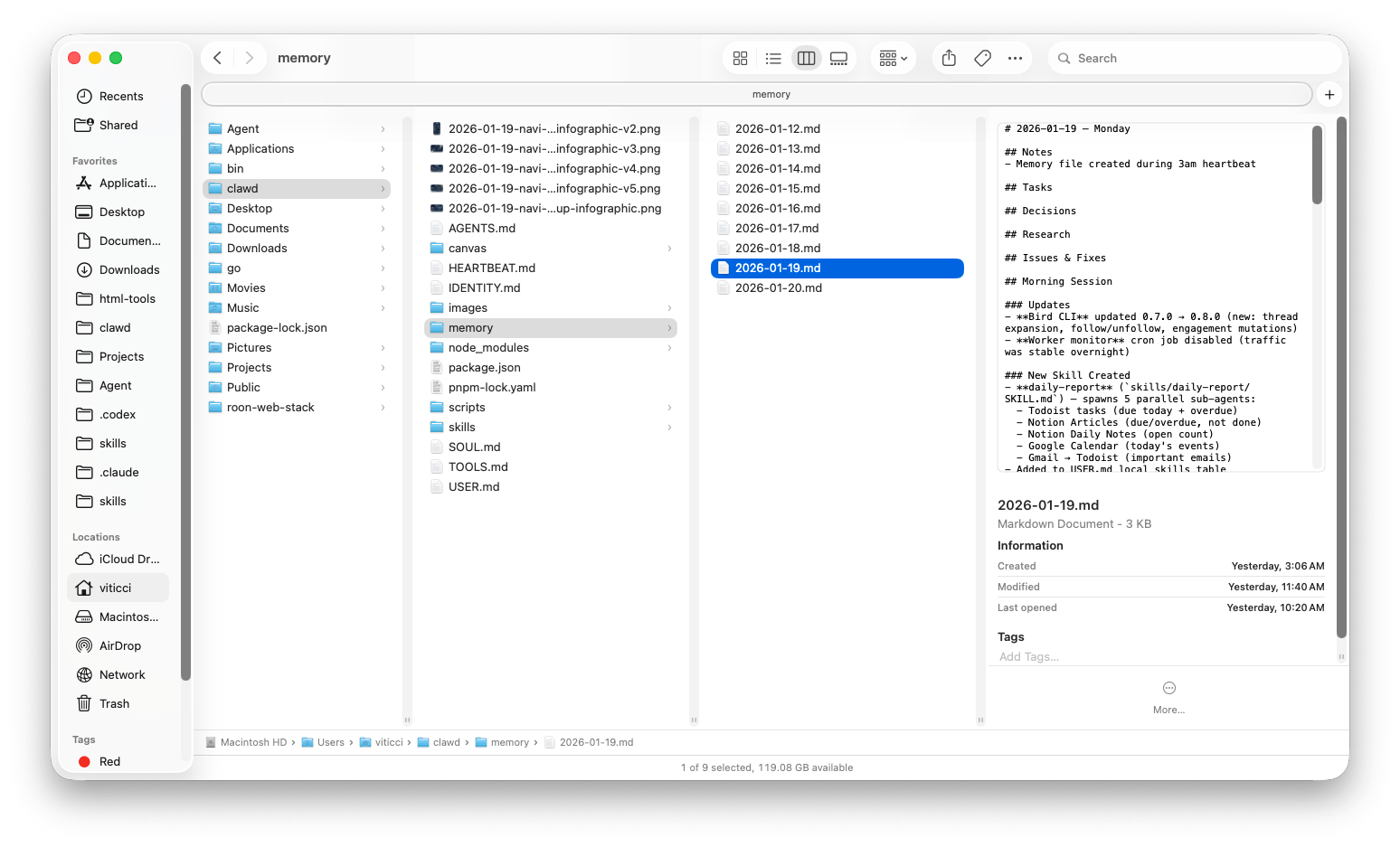

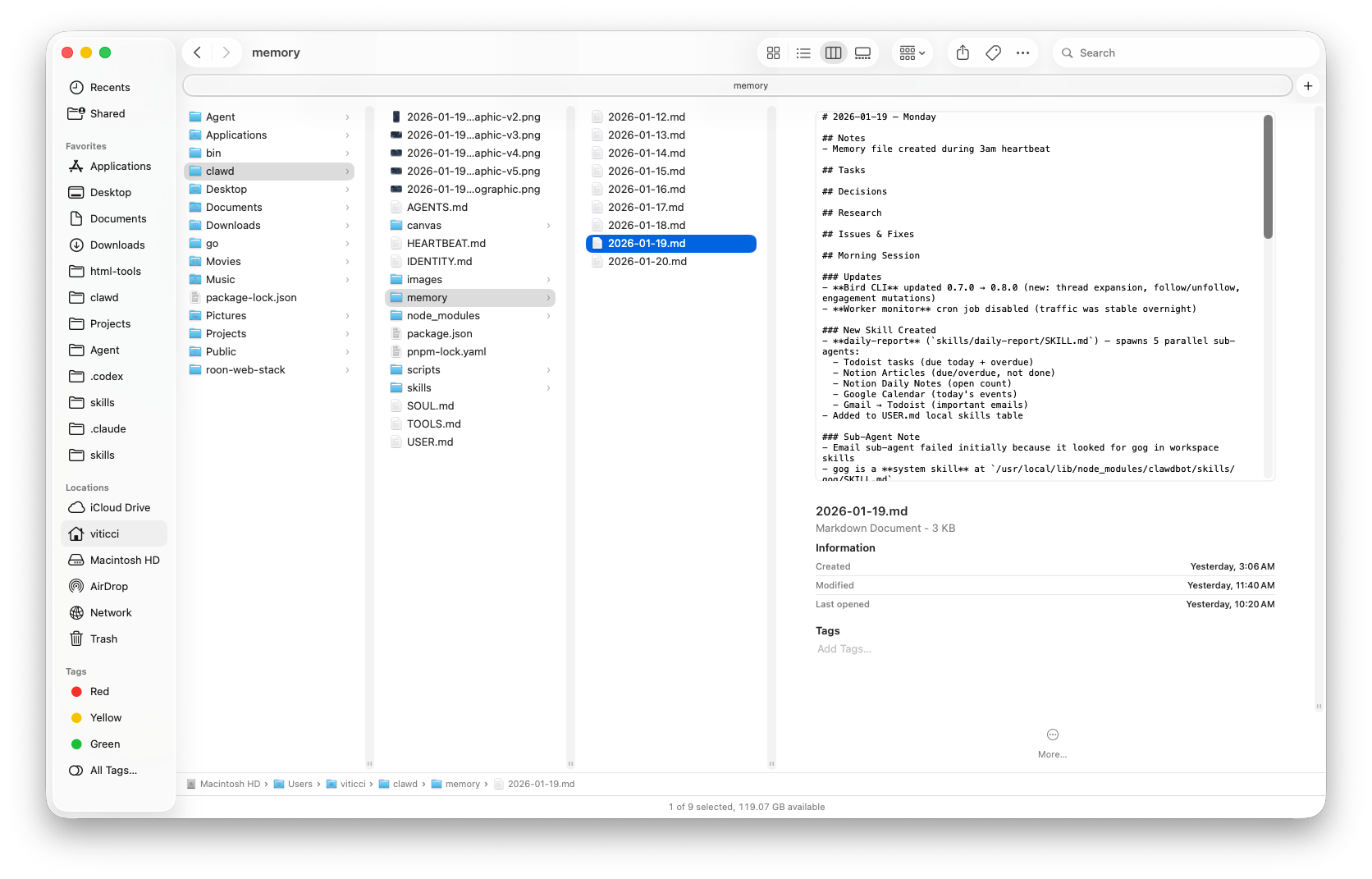

The “agent” part of OpenClaw is key, however. OpenClaw runs entirely on your computer, locally, and keeps its settings, preferences, user memories, and other instructions as literal folders and Markdown documents on your machine. Think of it as the equivalent of Obsidian: while there is a cloud service behind it (for Obsidian, it’s Sync; for OpenClaw, it’s the LLM provider you choose), everything else runs locally, on-device, and can be directly controlled and infinitely tweaked by you, either manually, or by asking OpenClaw to change a specific aspect of itself to suit your needs.

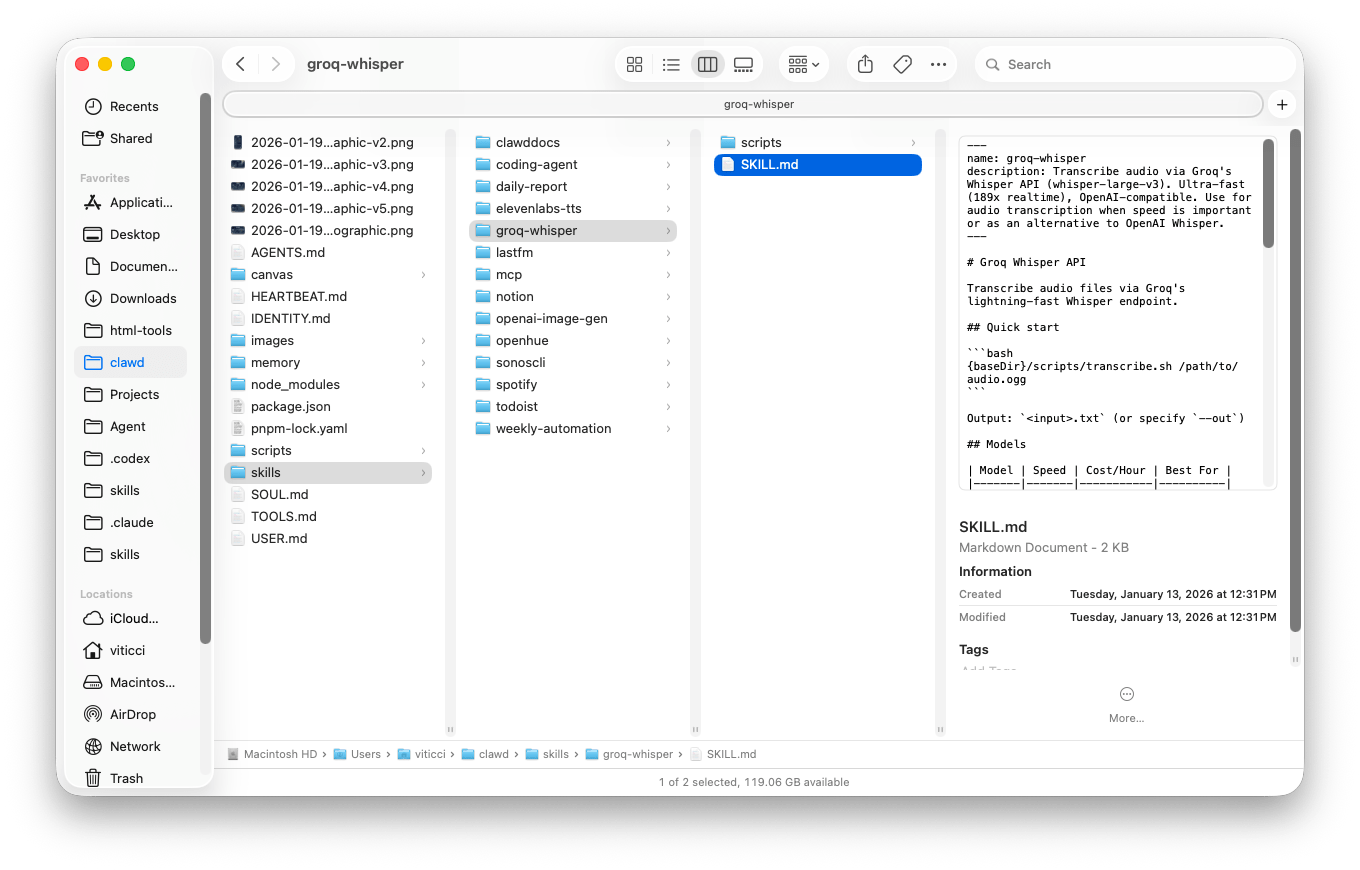

Which brings me to the most important – and powerful – trait of OpenClaw: because the agent is running on your computer, it has access to a shell and your filesystem. Given the right permissions, OpenClaw can execute Terminal commands, write scripts on the fly and execute them, install skills to gain new capabilities, and set up MCP servers to give itself new external integrations. Combine all this with a vibrant community that is contributing skills and plugins for OpenClaw, plus Steinberger’s own collection of command-line utilities, and you have yourself a recipe for a self-improving, steerable, and open personal agent that knows you, can access the web, runs on your local machine, and can do just about anything you can think of. All of this while communicating with it using text messages. It’s an AI nerd’s dream come true, and it’s a lot to wrap your head around at first.

To give you a sense of what’s possible: I asked OpenClaw to give itself support for generating images with Google’s Nano Banana Pro model. After it did that (OpenClaw even told me how to securely store my Gemini credentials in the native macOS Keychain), I asked Navi to give itself a profile picture that combined its original crustacean character with Navi from The Legend of Zelda. The result was a fairy crab featuring the popular “Hey, Listen!” phrase from the videogame, which it preemptively found on the web via a Google search:

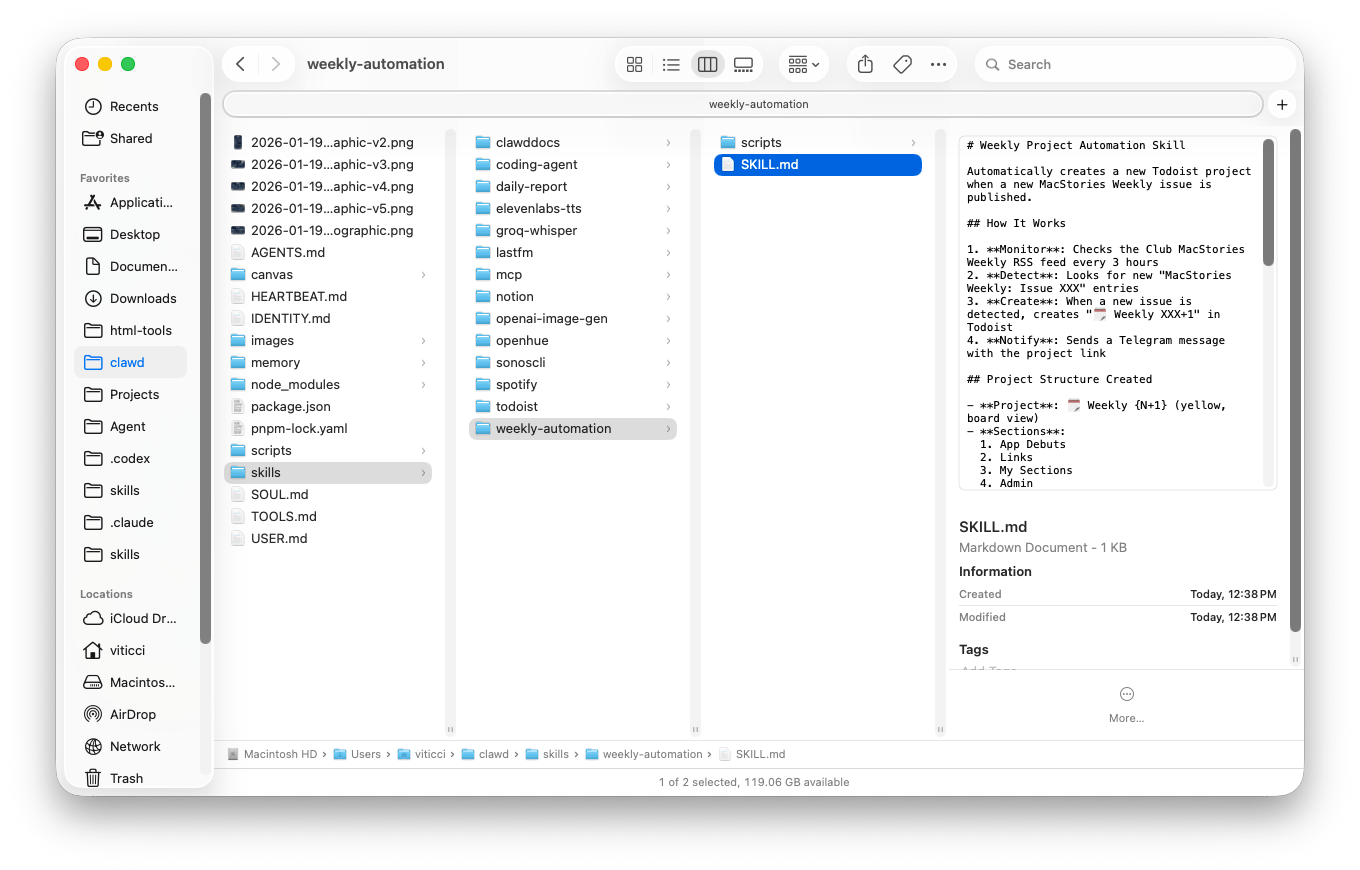

I then went a step beyond: I asked Navi to assess the state of its features and use Nano Banana to create an infographic that described its structure. Since OpenClaw is running on my computer and its features are contained in folders, OpenClaw scanned its own /clawd directory in Finder, went to Nano Banana, and produced the following image:

It’s pure AI slop, but it also shows how OpenClaw is aware of its configuration and how it is structured in Finder.

As you can tell from the image, I’m barely scraping the surface of OpenClaw’s abilities here. “Memory files” are, effectively, daily notes formatted in Markdown that OpenClaw auto-generates each day to keep a plain text log of our interactions. This is its memory system based on Markdown which, if I wanted, I could plug into Obsidian, search with Raycast, or automate with Hazel in some other way.

The integrations are, by far, the most fun I’ve had with an LLM in recent years. In keeping with the “you can just do things” philosophy we’ve discussed on AppStories lately, if you want OpenClaw to give itself a piece of functionality that it doesn’t have by default, you can just ask it to do so, and it’ll do it for you. Case in point: a while back I shared a shortcut for Club MacStories members that quickly transcribes audio messages using the Whisper model hosted on Groq. I grabbed a link to the article, gave it to Clawd, and told it that I wanted it to give itself support for transcribing Telegram’s audio messages with that system. Two minutes later, it created a skill that adapted my shortcut for Clawd running on my Mac mini.

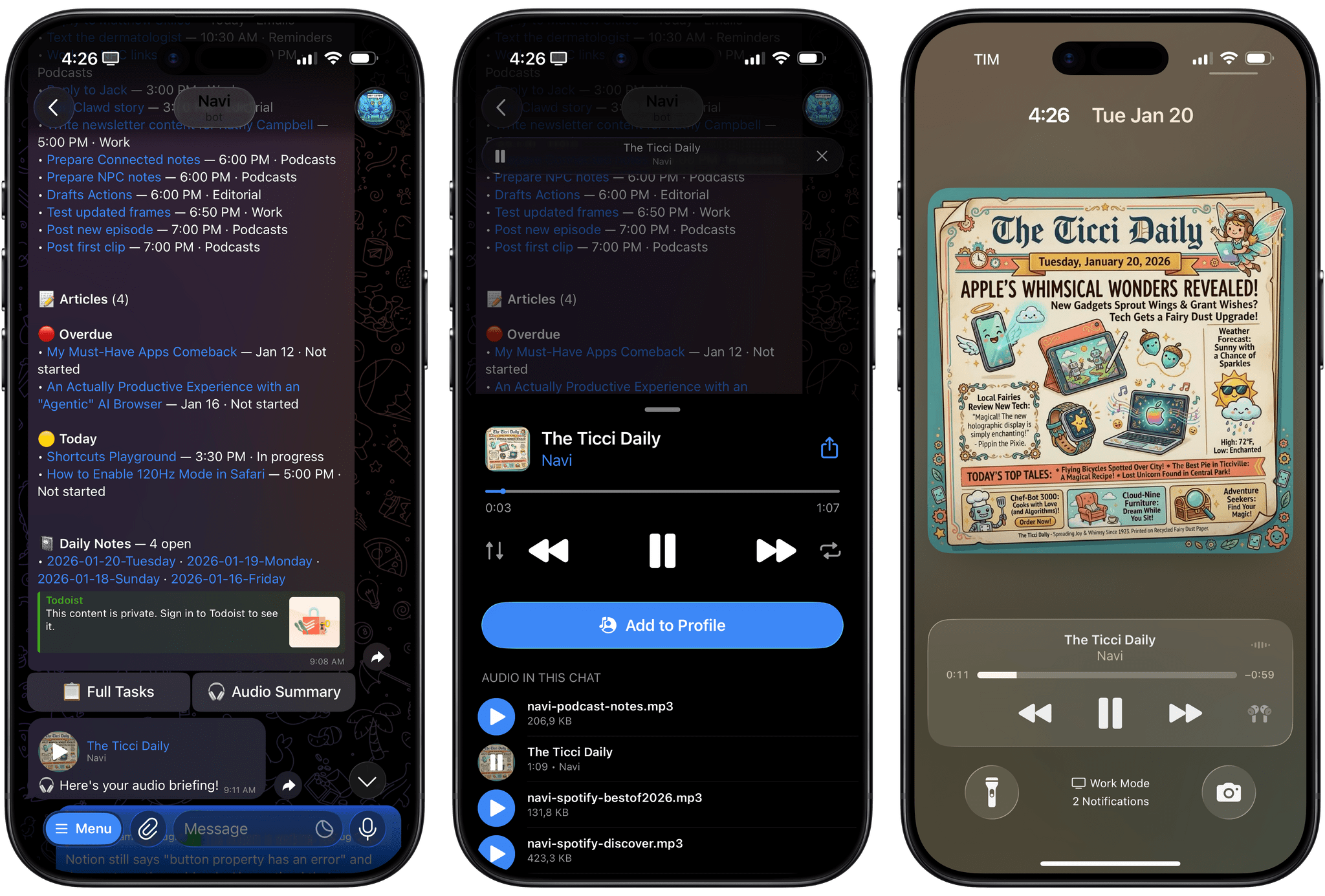

Then, I went a step beyond: like any good assistant, I wanted to make sure that if I issued a request with voice, Navi would also respond with voice, and if I sent a written request, Navi would reply with text. At that point, OpenClaw went off to do some research, found the ElevenLabs documentation for their new TTS model, asked me for ElevenLabs credentials, and created three test voices with different personalities for me to choose from. I chose one, fine-tuned it a little bit, and a few minutes later, Navi had a “voice” to use for future audio replies. Now, when I want to ask my assistant something but I’m busy doing something else and can’t type, I just send it a brain dump as an audio message on Telegram and, a few seconds later, I have a reply ready for me to listen to.

Every morning, OpenClaw sends me a daily report based on my calendar, Notion, Todoist, and more. It also sends me an audio version of the report that features silly artwork created by Nano Banana each day.

Being able to dictate messages in either Italian or English – or a mix of both! – for my assistant running in Telegram has been amazing – especially when you consider how the iPhone’s own Siri is still not multilingual today, let alone capable of understanding user context or performing long-running tasks in the background.

Still not impressed? How about this:

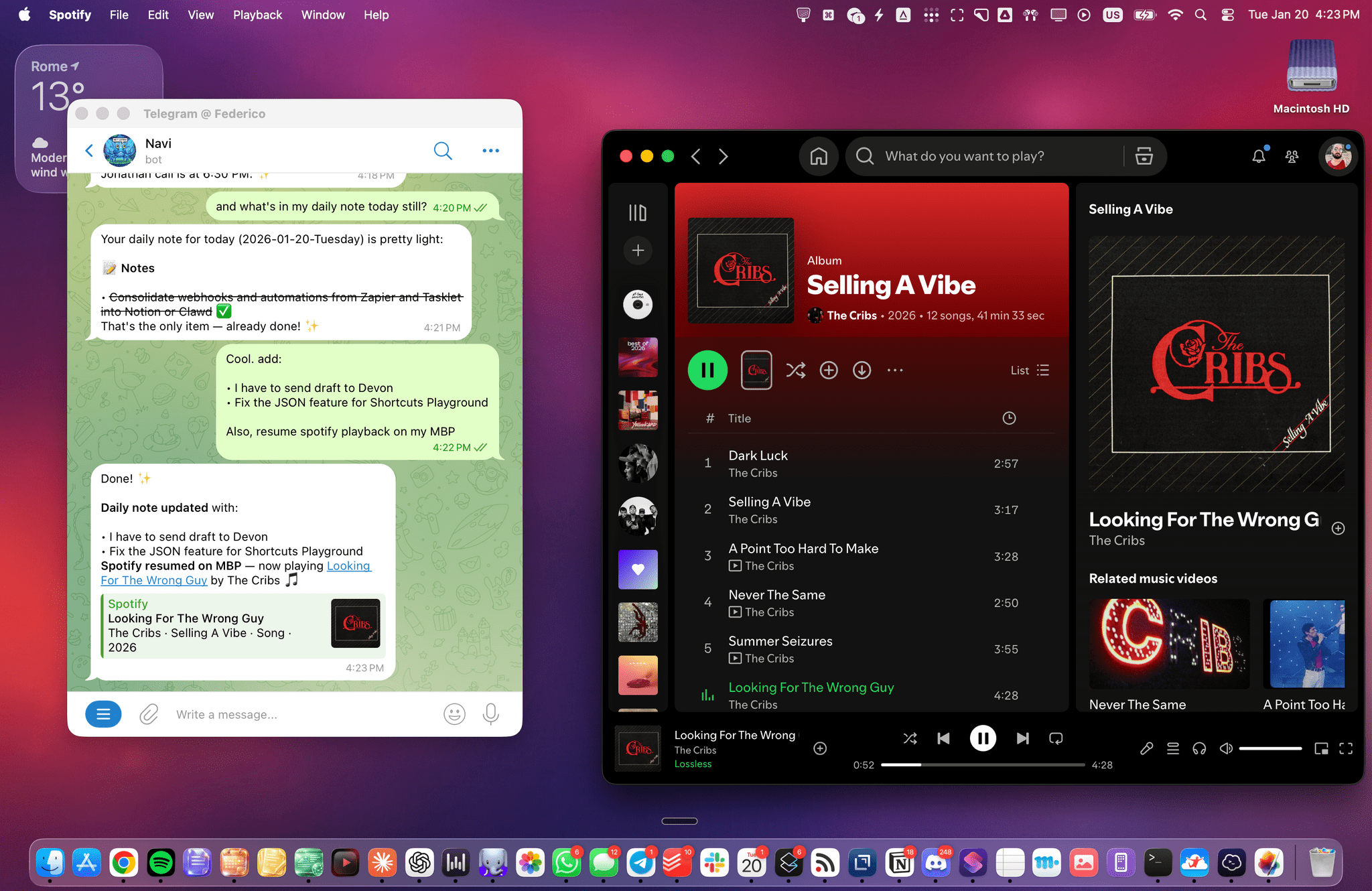

Last night, I wondered if I could replace some automations I had configured years ago on Zapier with equivalent actions running on my Mac mini via Clawd, to save some extra money each month. One of them, for instance, was a “zap” that created a project for the next issue of MacStories Weekly in my Todoist soon after we send the newsletter each Friday. It does so by checking an RSS feed, adding 1 to the issue number, and creating a new project via the Todoist API. I asked Clawd if it was possible to replicate it and, surely enough, it outlined a plan: we could set up a cron job on the Mac mini, check the RSS feed every few hours, and create a new project whenever a new issue appears in the feed. Five minutes of back and forth later, Clawd created everything on my Mac, with no cloud dependency, no subscription required – just the task I asked for, pieced together by an LLM with existing shell tools and Internet access. It makes me wonder how many automation layers and services I could replace by giving Clawd some prompts and shell access.

All of this is exhilarating and scary at the same time. More so than using the latest flavors of Claude or ChatGPT, using OpenClaw and the process of continuously shaping it for my needs and preferences has been the closest I’ve felt to a higher degree of digital intelligence in a while. I understand now why Fidji Simo, CEO of Applications at OpenAI, wrote that AI labs should do much more to leverage the capabilities of models (address the “capability overhang”) to build personal super-assistants. When I’m using ChatGPT or Claude, the models are constrained by the features that their developers give them and we, the users, can’t do much to tweak the experience. Conversely, OpenClaw is the ultimate expression of a new generation of malleable software that is personalized and adaptive: I get to choose what OpenClaw should be capable of, and I can always inspect what’s going on behind the scenes and, if I don’t like it, ask for changes. Being able to make my computer do things – anything – by just talking to an agent running inside it is incredibly fun, addictive, and educational: I’ve learned more about SSH, cron, web APIs, and Tailscale in the past week than I ever did in almost two decades of tinkering with computers.

Working with OpenClaw on my MacBook Pro. The assistant has access to my Notion and can even control Spotify playback via a Spotify integration.

OpenClaw also serves as a shining example of what happens when you give modern agents (with the right harness) access to a computer: they can just build things and become smarter for specific users (but not more intelligent in general) via quasi-recursive improvement. It’s no wonder that all AI companies have noticed, and every major feature launch these days is about a virtual filesystem sandbox or CLI access.

As I argued on AppStories, I believe that the repercussions of all this will soon ripple through the various app stores, and we’ll need to have serious conversations about the role of app developers going forward. OpenClaw is a boutique, nerdy project right now, but consider it as an underlying trend going forward: when the major consumer LLMs become smart and intuitive enough to adapt to you on-demand for any given functionality – when you’ll eventually be able to ask Claude or ChatGPT to do or create anything on your computer with no Terminal UI – what will become of “apps” created by professional developers? I especially worry about standalone utility apps: if OpenClaw can create a virtual remote for my LG television (something I did) or give me a personalized report with voice every morning (another cron job I set up) that work exactly the way I want, why should I even bother going to the App Store to look for pre-built solutions made by someone else? What happens to Shortcuts when any “automation” I may want to carefully create is actually just a text message to a digital assistant away?

I don’t know the answers to these questions right now, but we’re going to try and unpack all of them on AppStories and MacStories this year.

For now, I’ll stop here: OpenClaw is an outstanding project that I can’t recommend tinkering with enough if you find the idea even remotely interesting. OpenClaw has shown me that we’ve barely begun to tap into the potential of LLMs as personal assistants. There’s no going back after wielding this kind of superpower.